This article is part of the publication 15 Years of REDD:

A Mechanism Rotten at the Core

>>> Download the publication in pdf

‘Carbon concessions’ established to generate and sell carbon credits are also deeply eroding communities’ structures, their organization and community reproduction. This is the story of the Bapinang Hilir village in Indonesia. Despite being located outside the ‘Katingan REDD+ project’ concession area, it has been identified as inside the verified project zone by the certification schemes (VCS and CCBA). The article explores how the concession owners have profited from this inclusion at the cost of the Bapinang Hilir villagers.

Bapinang Hilir Village is located in the administrative area of Pulau Hanaut District, Kotawaringin Timur (East Kotawaringin) Regency, Indonesia. It is one of the thirteen regencies which comprise the Central Kalimantan Province on the island of Kalimantan. Its location in the estuary, bordering the Katingan River and the Mentaya River, accounts for the tidal swamp area with a layer of peat and pyrite. This area began to be inhabited by migration flows due to the coal extraction in South Kalimantan 150 years ago through which the Banjarese People were evicted and displaced to the Mentaya River, a place where the capital circuit of crop commodities (coconut and rubber) was being prepared by the colonial administration.

The historical context in Bapinang Hilir post migration characterizes the conflicts over the frontier land between the capital circuits and the people living in this area. Capital injected from the outside mainly results in the expansion of industrial activities that devour the living spaces. Peatlands, being sensitive to change, clearly illustrate this ecological destruction, where the vortex of exploitation of humans and their environments is increasingly exacerbating the experience of marginalization for communities. In the last decade, the remaining commons have been increasingly enclosed for the carbon trading business.

This new chapter in the history of Bapinang Hilir shows the absolute expansion of capital accumulation that consumes not only the ecological life spaces, but also the reproduction of society. (1) The excess (of pollution) that has been continuously sown by the financial and industrial capital of northern countries for the past two centuries is now considered a (climate) crisis and, in capital logic, this has become a commodity. This in turn has allowed the creation of carbon concessions that generate and sell carbon credits. Ironically, this model transfers the responsibility for ‘reducing’ emissions to small farmers in Bapinang Hilir. Yet, the carbon credits being generated are not reducing but in fact are only supposed to be compensating further pollution somewhere else.

The initial conclusion about a business scheme that does not only sell peat forest landscapes but also changes the community structures and organization -as required by carbon certification schemes- indicates the commodification of community reproduction. Thus, when referring to the carbon concessions established for selling carbon credits to largely northern countries and corporations, one cannot escape from also referring to how space (reproductive society and nature) is also systematically being commodified.

Katingan REDD+ Project

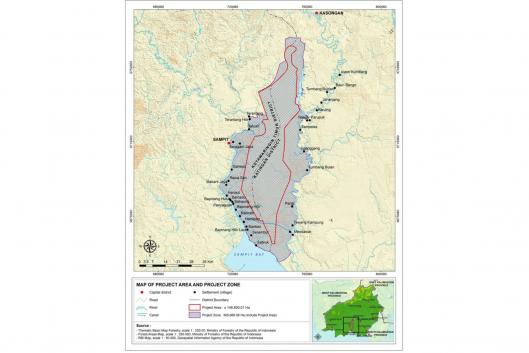

The land that is left without economic concessions or extractive activities is still considered communal land. However, since 2016, this remaining area has been under the control of PT Rimba Makmur Utama (RMU) for the Katingan Peatland Restoration and Conservation Project or Katingan REDD+ project, through the concession of the Ecosystem Restoration Timber Forest Product Utilization Permit (IUPHHK-RE). The Indonesian company RMU was founded in 2007 with the idea of profiting from forest conservation activities through carbon trading. RMU applied in 2008 for Ecosystem Restoration Concessions (ERC) (2) covering an area of 227,260 hectares located in Katingan and Kotawaringin Timur Regencies. Yet, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry only issued the concession in Katingan Regency in 2013, and the other in 2016, covering an area of 149,800 hectares (see figure 1). (3) When calculating the area of the Project Zone, which includes the area outside the Ecosystem Restoration Concessions, the area reaches 305,669 hectares, making the Katingan REDD+ project the largest emission reduction project in the world. The project has received the certification of Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and the Climate, Community & Biodiversity Alliance (CCBA).

Although RMU's concession area is of 149,800 hectares, the total area accounted for as the VCS and CCBA verified project zone is of 305,669 hectares. (3) Before the carbon credits could be sold, RMU relied on investments from various organizations and companies, including The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, USAID Indonesia Forest and Climate Support, the Global Environmental Facility, the Clinton Foundation, Norway’s development bank NORAD and the Puter Foundation, which is RMU's partner for community development activities.

In addition to the sale of carbon credits, RMU through the Puter Foundation receives funds from various companies and foundations to carry out community empowerment programs. The ones emerging in Bapinang Hilir include participatory mapping, empowerment of coconut sugar farmers, and programs encouraging the community to switch to organic horticultural farming. These funds can be seen as a way for RMU to meet the cost requirements for the certification schemes and as an incentive to make it easier to trade the carbon credits.

The carbon credits are calculated based on the scenario of the threat of deforestation from industrial plantation concessions, community cultivation rights and forest encroachment by the community. The amount of carbon dioxide that is expected to be avoided with the REDD+ project, according to the project document, makes the base for the amount of credits that can be sold. This is supposed to be based on calculations in the concession area (or project area) between a baseline scenario without the project and an imagined scenario with the project. However, this calculation also incorporates areas outside the concession, or what is referred to as the project zone, which includes the communities’ settlements and agricultural land. These areas are a deduction factor for the carbon credits that can be sold. RMU itself acknowledges that these bear risks to land tenure and local politics and suggests that these can be reduced through approaches and agreements among communities. (3)

The VCS certification obtained by RMU has conditions. One of which is to ensure that the project does not have negative impacts on local communities and to encourage their participation in the project development and implementation process. The CCBS certificate is aimed to guarantee that the project improves the welfare of the people in the project zone. This is calculated by comparing scenarios of community welfare without activity intervention and community welfare after intervention. A CCBS certificate can increase the value of a carbon credit by around US1.6 dollars per tCO2e (from an initial price of around 2.3 to 3.9 dollars as of 2016). In addition, this certificate is a determining factor for reducing the risks that could impact the amount of carbon that can be sold, as well as part of an emission reduction scenario that arise due to community encroachment. It is estimated that RMU has the potential to generate around US1.7 billion dollars for the 60-year concession period, without taking into account the grant funds that they are also obtaining. (3)

RMU started interacting with communities through the Puter Foundation in 2012, using USAID funds, for mapping the communities’ resources and livelihoods and preparing them to collaborate in the carbon business. This was the initial stage for the company to attempt to sign a Memorandum of Understanding with the village government. After signing the MoU, the village would receive 100 million Indonesian rupiahs (around US7 thousand dollars) as well as two million rupiahs (around US140 dollars) per month for strengthening the village apparatus. Villagers could also submit proposals for the development of their economic activities. The community business development carried out is based on an agricultural program that introduces organic fertilizers and prohibits burning and using chemicals.

The first initiation stage was rejected by almost all village governments, creating RMU many difficulties to obtain a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). This resistance was mobilized by the coconut elite who controlled village and sub-district administrations as well as the Hanaut Island Dayak Misik Farmers Group. (4) This refusal was prompted by the news circulating in the community in Katingan Regency that residents had difficulty accessing the forest due to the gradual restrictions on the use of residents in the concession area by RMU. (5) However, the provision of funds to the village government encouraged the aspiration of other village governments to cooperate with RMU as well as to develop suspicion between the village and the Dayak Misik Group.

The Dayak Misik Group, as the only customary group institution with an interest in expanding land through the issuance of the Certificate of Customary Land, is hampered by the control of the communal land by RMU. Other farmers who are not part of the Dayak Misik Group, like village administrations and owners of large coconut plantations in Bapinang Hilir, tend to support Dayak Misik because they consider the MoU between the village and RMU has meant the handing over of communal land and prohibiting villagers’ entry into their forest. The emergence of appeals (6) not to carry out activities that have the potential to reduce carbon credits, such as planting palm oil, harvesting wood and hunting, makes some farmers feel even more threatened (7) by the MoU. In addition, RMU’s control of land also makes land scarce.

In 2017, the sub-district administration was cleared of the coconut elite and the elected sub-district head was deemed to facilitate the process of signing the MoU. After the sub-district head was changed, almost all villages signed a cooperation agreement with RMU because they were tempted by other villages that had been given money.

Carbon business and human commodification

The emergence of carbon as one more capitalist commodity changes the labour and productive relations in the countryside dramatically. Peasants, who had a certain level of autonomy, controlled the means of production and worked through their own power, are turned due to the REDD+ project into petty commodity producers. (8) By loosing their autonomy, they have to produce commodities to get money in exchange for buying other commodities for consumption needs and thus integrate into the capitalist market economy, depending on the money they get from selling their labour.

The people of Bapinang Hilir and the indigenous people of Kalimantan in general have specific arrangements and divisions of labour in terms of burning shrubs before planting. (9) This is done in a way that the fire does not emit smoke and does not spread to other farmers' gardens. During the fire season, people who have gardens usually use their labor to prevent their crops from being devoured by the fire. Burning bushes became a contested issue in Bapinang Hilir in 2019-2020 due to the threat of 25 years imprisonment and a fine of 2 billion Indonesian rupiahs (around US14 thousand dollars) to who initiated a fire. In consequence, farmers generally switched to using herbicides to remove grass or, in small amounts, to secretly burn land. Land fires, which means uncontrolled fires, are generally caused by abandoned land and spread by the expansion of large-scale monoculture tree plantations, like oil palm and acacia.

The 2015 land fires that left hard soils with high acidity and burned food gardens, was a result of the capital circuits that emerged 150 years ago. Along with this is the class differentiation. Small farmers are increasingly marginalized with land fires due to the hard and high acidity soil, elites who control the village administrations and have very large coconut plantations accumulate more land and middle farmers expand their oil palms. Marginal rice farmers are left to use herbicides because they are forbidden to use fire, significantly increasing the costs of growing rice and damaging the soil and water sources. One year after the big fires, the carbon business is annexing and enclose the remaining uncultivated land through ecosystem restoration concessions. The inspection of the carbon business is not only about land enclosures, restricting access to local communities, but also on how community reproduction is commodified.

The baseline and trajectory assessment of communities outside the concession area as well as the forms of intervention proposed and agreed upon by the certifier are the origins of the valuation of community reproductive activities. The reproduction in question does not only talk about marginal communities experiencing a crisis, but also the dynamics of agrarian change. What is being sold does not only cover marginal farmers, but also issues related to community habits (burning grass), long-term labour reproduction (education) and the class dynamics in rural areas (vacant land, restricted access by elites, marginal farmers).

Meanwhile, the REDD+ Katingan project is selling carbon credits to multinational polluters like oil company Shell and airline KLM. These companies claim to be ‘carbon neutral’ because they buy carbon credits generated by projects that in fact are structurally changing communities’ fabrics and organization. (10)

The implication is a metabolic fracturing and the accompanying dynamics (ecological changes, class differentiation and marginalization) of being incorporated as community's reproductive commodities. The interventions listed in the certificate validation report shows that the carbon business is not only commodifying the vast carbon landscape, but also producing new spaces where ecology (of which humans are a part) itself becomes a commodity.

Izzuddin Prawiranegara,

Agrarian Resources Centre, Indonesia

(1) The reproduction of society in question refers to the social relations and processes that ensure or sustain social structures over time. See further in: Bachriadi, Dianto. 2020. 24.2: Manifesto Penataan Ulang Penguasaan Tanah ‘Kawasan Hutan’. Bandung: ARCBooks.

(2) Indonesia: What is an Ecosystem Restoration Concession?

(3) RMU. 2016. Katingan Peatland Restoration and Conservation Project: Project Description VCS Version 3, CCB Standards Third Edition. Washington, DC: Verified Carbon Standards dan CCB Standards.

(4) The Dayak Tani Misik Group is part of the Coordination Forum of the Dayak Misik Farmers (FKKT) Group (hereinafter referred to as the Dayak Misik) which was established in 2014 to provide land and forest security to the Dayak people and to prevent customary lands from being controlled by migrants and companies. The FKKT Dayak Misik has a program of handing five hectares of land to members of the Dayak Misik group through the issuance of a Certificate of Customary Land. In some places, the Dayak Misik is used as a scheme to fight against large-scale land tenure by mining corporations and palm oil. In Bapinang Hilir, the management of the Misik Dayak is controlled by an elite coconut family and its members are not limited to Dayak people, but also include Banjar and Malay people.

(5) Prior to obtaining a concession in East Kotawaringin Regency, RMU obtained a concession in Katingan Regency in 2012. After obtaining the VCS certificate, RMU first succeeded in obtaining a Memorandum of Understanding with the majority of village governments in Katingan.

(6) This appeal is accompanied by training on the cultivation of organic food crops and vegetables to farmers selected by RMU field officers. After the farmers returned to their respective areas, the farmers were given funds to establish pilot fields for food crops and organic fertilizers.

(7) This threat creates high suspicion of outsiders which makes it difficult to interact and gain trust with the people of Bapinang Hilir. In order to detect whether outsiders are on the side of RMU or not, farmers ask questions regarding the permissibility of burning grass on their land.

(8) The term peasant refers to a person who cultivates land in the countryside, controls the means of production, works through his own power whose surplus production is taken by the authorities and the rest is used to exchange the products produced (from labor) for goods that - culturally - considered equal. While petty commodity producers are solely a group of people involved in farming for the purpose of producing commodities or people who are involved in capitalist commodity production relations in agriculture. Even though it seems inconsistent, especially when it comes to finding Indonesian equivalents, here petty commodity producers will also be referred to as ‘farmers’.

(9) For comparison, see Dove, Michael, R. 1988. Sistem Perladangan di Indonesia: Suatu Studi-studi Kasus dari Kalimantan Barat. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press. And, Dove, Michael R. "Theories of swidden agriculture, and the political economy of ignorance" Agroforestry systems 1.2 (1983): 85-99, which provides a very detailed description of the land burning techniques used by the Dayak people in West Kalimantan in preparing agricultural land. Watson, G. A. 1984. “Utility Of Rice Cropping Strategies In Semuda Kecil Village, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia.” Workshop on Research Priorities in Tidal Swamp Rice. Los Banos: International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). 49-67, also describes how people in the Mentaya River watershed cultivate rice through burning.

(10) https://wrm.org.uy/articles-from-the-wrm-bulletin/section1/driving-carbon-neutral-shells-restoration-and-conservation-project-in-indonesia/

References:

- Prawiranegara, Izzuddin. 2020. Dari marginal menjadi lebih marginal: Pendalaman Metabolic Rift di Lahan Gambut (unpublished). Bandung: Agrarian Resources Center.

- Großmann, Kristina. 2019. “‘Dayak,WakeUp’: Land, Indigeneity, and Conflicting Ecologies in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia.” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 175 (2019) 1–28 1-28.

- Hamrick, Kalley, dan Melissa Gallant. 2017. Unlocking Potential State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2017. Washington, DC: Forest Trends' Ecosystem Marketplace.

>> Back to the the publication 15 Years of REDD: A Mechanism Rotten at the Core index