Mining is a short-term activity with long-term effects. There can be no doubt that when it takes place in forest zones, it is a factor of degradation. It is calculated that, together with oil prospecting, mining is threatening 38% of the last stretches of the world's primary forests.

Mining activities are carried out in various stages, each of them involving specific environmental impacts. Broadly speaking, these stages are: deposit prospecting and exploration, mine development and preparation, mine exploitation, and treatment of the minerals obtained at the respective installations with the aim of obtaining marketable products.

During the prospecting phase, among other activities having an impact on the environment are the preparation of routes of access, topographic and geological mapping, establishment of camps and auxiliary facilities, geophysical works, hydro-geological research, opening up of reconnaissance trenches and pits, taking of samples.

During the exploitation phase, the impacts depend on the method used. In forest zones, the mere deforestation of the land with the consequent elimination of vegetation --greater in the case of opencast mines-- has short, medium and long-term impacts. Deforestation not only affects the habitat of hundreds of endemic species (many doomed to extinction), but also the maintenance of a constant flow of water from the forests towards other ecosystems and urban centres. Deforestation of primary forests causes a rapid and fluid runoff of rainwater, increasing flooding in rainy periods because the soil cannot contain the water as it does when covered by forest.

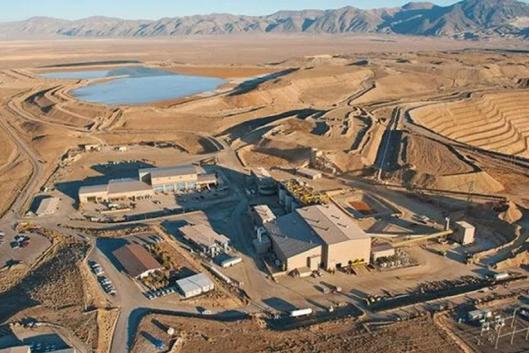

In addition to the area disturbed by the excavation, the damage caused by mines on the surface due to the consequent erosion and silting (sedimentation of the watercourse beds) is made more serious due to heaps of rock residues lacking economic value (known as tailings), that usually form great mounds, sometimes larger than the area given over to excavation.

The enormous consumption of water required by mining activities generally reduces the water table around the site drying up wells and springs. Water usually ends up being contaminated by the acid drainage, that is, exposure to air and water of the acids formed in certain types of ore --particularly sulphuric acids-- as a result of mining activities, which in turn react with other exposed minerals. A self-perpetuated dumping of acid toxic material is generated that can go on for hundreds or even thousands of years. Furthermore, the small particulates of heavy metals that with time separate from the waste, are disseminated by the wind, landing on the soil and in the beds of watercourses and slowly integrating the tissues of living organisms, such as fish.

Hazardous chemicals used in the various stages of metal processing, such as cyanide, concentrated acids and alkaline compounds, although supposedly controlled, usually end up, one way or another, in the drainage system. The alteration and contamination of the water cycle has very serious side effects that affect surrounding ecosystems --especially more so in forests-- and people.

Air pollution can be caused by the dust generated by mining activities, a serious cause of illnesses, generally in the form of respiratory troubles in people and asphyxia of plants and trees. Furthermore, usually, a release of gases and toxic vapour takes place: sulphur dioxide --responsible for acid rain-- is produced because of metal treatment, and carbon dioxide and methane --two of the main greenhouse effect gases causing climate change-- are also released, due to the burning of fossil fuels and the creation of artificial lakes for the hydroelectric dams, built to provide energy for the casting ovens and refineries.

Additionally, mining activities consume enormous quantities of wood for their construction --in the case of underground mines-- and as a source of energy for mines with charcoal-fuelled casting ovens. Also, when carried out in remote zones, mining activities imply major works such as road building (opening access to the forests), ports, mining villages, the deviation of rivers, construction of dams and energy generating plants.

The deafening sound of the machinery used in mining and the blasting cannot be considered as minor impacts either because they create conditions that may become unbearable for the local populations and the forest wildlife.

It is argued that mining is vital for industrialization, because it provides raw material and sources of energy. However, the present disproportionate concentration of investment on gold and diamond-seeking, marginal for industrial production, refute the sector's social justification for its activities. In 2001, 82% of the gold refined found its way to the jewellery market and it is worth remembering that to make a gold ring, the average amount of rock waste generated in a mine is over 3 tons. In the United States, the Pegasus Gold company caused the Spirit Mountain in Montana to disappear, replacing what had been a sacred tribal place by an opencast gold mine. Over the next 1,000 years, the site will continue to distil acid into the region's watershed.

Throughout history, the various gold rushes have brought death and devastation to the local populations. From the Sioux of the Black Hills, to the Aborigines around Bendigo in Australia, the history of gold is tainted with blood; and today Amazonian tribes, like the Yanomami and Macuxi, the Galamsey of West Africa, and the Igorot of the Philippines, are similarly endangered.

Mining comes along with its promise of wealth and jobs, but millions are those throughout the whole world who can testify to the high social costs that it brings with it: appropriation of the land belonging to the local communities, impacts on health, alteration of social relationships, destruction of forms of community subsistence and life, social disintegration, radical and abrupt changes in regional cultures, displacement of other present and/or future local economic activities. All this is added to the hazardous and unhealthy working conditions of this type of activity.

It may be held that many of the affected communities have given their consent. However, it is hard to speak of previous, genuine informed consent, as they do not have the opportunity to fully understand what is waiting for them when they are asked to place their signature on the dotted line at the foot of a contract. For this reason, mechanisms to enable indigenous and local communities to effectively participate in decision-making processes are called for, together with legislation enabling them to reject this type of undertaking in their territories.

If there are people who want to wear gold anyway, or use it to fill cavities, or for micro-circuitry in computers and cell phones, that is all well and good but as someone proposed, take it from recycled sources. Of the 125,000 tons of gold extracted from the ground, more than 35,000 tons lie in the vaults of central reserve banks. The US Federal Reserve holds 8,145 tons of gold, approximately 6% of all the gold ever mined. What would be better than recycling it from the bank vaults!

Article based on information from: Undermining the forests. January 2000, by FPP, Philippine Indigenous Peoples Links and WRM, http://www.wrm.org.uy/deforestation/mining.html ; The decade of destruction, Mines & Communities Website, http://www.minesandcommunities.org/Company/decade.htm ; Global Mining Snapshot, April 2003; Making a Molehill out of a Mountain, 4 April 2003, Mineral Policy Center, e-mail: mpc@mineralpolicy.org ; http://www.mineralpolicy.org ; Los Impactos Ambientales de la Minería: Una Guía Comunitaria, http://andes.miningwatch.org/andes/espanol/guia/capitulo_1.htm ; New research on the impact of mining, Oxfam Community Aid Abroad, e-mail: enquire@caa.org.au , http://www.caa.org.au/horizons/august_2001/researchmining.html ; Fool's Gold: Ten Problems with Gold Mining, Project Underground, e-mail: project_underground@moles.org , http://www.moles.org/ProjectUnderground/reports/goldpack/fools_gold.html ; Indigenous Peoples and the Extractive Industries: A Call on the World Bank to Overhaul its Institution, Emily Caruso, Forest Peoples Programme, e-mail: info@fppwrm.gn.apc.org , http://forestpeoples.gn.apc.org/index.htm