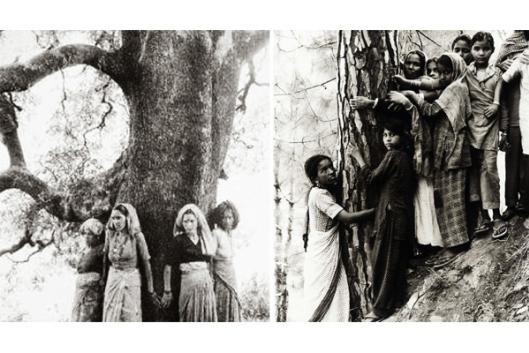

March 8 is not just a day to celebrate and give visibility to women’s struggles, it is also a day to remember and appreciate the valuable inspiration they provide for every other struggle today. One example is the Chipko women’s movement in India, and the struggle they have led for nearly 40 years to protect forests and resist tree monocultures in the Himalayan region, in the provinces of Garhwal and Kumaon. The brave struggle of these Indian women is still continuing.

The Chipko movement was inspired by a struggle that took place in India over 300 years ago and was led by a woman. In those days, members of the Bishnoi community in Rajasthan scarified their lives trying to save sacred khejri trees by hugging the tree trunks. In the 1970s the Chipko movement, a grassroots movement made up mainly of women, carried out similar resistance actions, embracing trees to prevent their felling by groups of loggers. The movement used (among other things) a poem from that historic time that says: “Embrace our trees, save them from being felled. The property of our hills, save it from being looted.” The first action of the Chipko movement took place in 1973, when local people marched into Mandal Forest beating drums to save 300 ash trees that were about to be felled by a timber company. When the chainsaw operators saw that the community was well-organized and determined to hug the trees, they backed off and did not cut down the trees. Many other victories followed.

This is an admirable example of struggle; without wishing to mythologize it, it contains lessons worth learning and strong, valuable inspiration to remember and share. For instance, prior to taking decisive action, the women examined and clearly identified the causes of deforestation on their lands: the goal of unstoppable deforestation and monoculture pine plantations is, above all, profit. They analyzed how these destructive activities caused floods and soil erosion, directly affecting traditional economic activities like agriculture and livestock herding. In the case of the Garhwal region, they became aware that the disappearance of native trees, especially banj trees, contributed decisively to the deterioration of the region’s ecology. Replacing the banj with pine monocultures further jeopardized the environmental stability of the region.

Ecological imbalance was affecting women, above all, since they carry out 98 percent of agricultural and herding activities, something that is very common throughout the developing world. In a context where sawmills and the exploitation of forests were increasing, the Chipko movement realized that forest conservation was essential for the continuation of the economic activities that were their livelihood. As one of the women leaders said: “Today I see clearly that installing sawmills in the mountains is a way of supporting the project to destroy Mother Earth. Sawmills have an insatiable appetite for trees and will raze the forests to satisfy it.” Forty years later, it is evident that timber extraction by logging companies, even though it is called “sustainable forest management” and is highly profitable, continues to destroy the world’s last regions of forest with valuable hardwood trees. These companies’ “appetites” can never be satisfied.

The movement illustrates a conflict between two opposing sides which is entirely contemporary: on the one hand, the ethic defended by the women of the Chipko movement, especially that of sharing, producing and nurturing life. When they talk about nature, they speak of “Mother Earth,” which expresses the feeling of belonging to the land, the forests and nature and the desire to care, not destroy. On the other hand is the desire for dominion over and exploitation of nature, reflecting the Western worldview which separates human beings from nature. This side advocates the “development” created by the money-as-capital economy, which has also created extreme poverty and addictions like alcoholism. It should be recalled that before women in the Chipko movement began to fight for the forests, they had begun the fight against alcohol which affected the life and health of their husbands, especially those who were actively engaged in logging activities, and so also affected the women and their families.

Finally, the movement showed the importance of feminism as a component in the struggle to conserve the forests and protect the environment. This was very important because at the same time the women were defending the trees, they were confronting their own husbands who worked for the logging companies and were felling the trees. The story is told that once a group of women of the Chipko movement confronted their own husbands because they were going to participate in deforestation. One of the men said, “You foolish women, how can you prevent tree felling by those who know the value of the forest? Do you know what forests hold? They produce profit and resin and timber.” The women sang back in chorus: “What do the forests hold? Soil, water, and pure air. Soil, water, and pure air, sustain the Earth and all she holds.”

The Chipko Movement shows that women’s liberation is not only about liberation from the oppression of the patriarchal societies that dominate the world, but also about the liberation of all men and women “colonized” by the economic logic of domination and the unlimited and irrational exploitation of nature by capital.

Source: Vandana Shiva. Staying Alive: Women, ecology and survival in India.

Kali for Women, 1988. http://gyanpedia.in/Portals/0/Toys%20from%20Trash/Resources/books/stayingalive.pdf